I have spent the past year working on revising my novel in

progress, Unspeakable Things, having had it assessed by a Creative

Consultancy attached to Annette Green Author’s Agency. I paid for this service

with a certain amount of trepidation since, if someone is making money out of

you, you always have that niggling suspicion that they may be serving their

interests rather than yours.

I now feel that going to a consultant was the best thing I

could have done. What returned was a detailed, 18-page assessment that was like

a mini-course in creative writing, but focused entirely on my novel. It was

honest, impartial, clear, no-holds-barred and yet sensitively worded and always

encouraging. When I sent the work out, it was like calling out from my writer’s

closet, with very little idea as to whether my writing was going well or not.

In the year since then, I have pored over every word of those 18 pages and

worked to correct every flaw. I have come out of my closet to write this blog,

which I even tell people about. In public!

Thanks to the assessment and the work of revision it has inspired, I

have a new confidence in my novel. I can see that it is working better, and I

know why.

Since I trawl other writer’s blogs in the hope of finding

helpful tips on writing, I thought I would share the best tips I received. Although

the assessment was directed specifically at my novel, the basic pointers in it

are universal, and will be helpful to anyone embarking on a full-on revision.

Let’s face it, at that vital stage of writing, we need all the help we can get!

Tip 1 Flesh out your characters. The consultant went through

each character in turn, but beginning with my heroine, Sarah, commented, ‘As a

character she needs more depth, more fleshing out... To some extent this is

true of all the characters. They read as if you have given them just enough

inner life to make the plot work, whereas memorable, fascinating characters

give the impression of having a life outside the page.’

I had converted the

story of Unspeakable Things into a novel, having first written it as a

screenplay, and had very much enjoyed writing what I thought of as the ‘interiors’

of the characters, which in a screenplay can only be suggested through dialogue

or stage directions. Now I saw that I had not created these interior lives

fully enough. I needed to think through every aspect of my characters’ pasts,

motivation and relationships so that their responses to the events of the story

would make perfect, believable sense. The reader needed to feel, when a

character behaved in a certain way, that yes, that is exactly how they would

respond, for many valid and credible reasons.

I began a dossier on each character and worked on each of

their backstories. I developed their working lives, gave them relevant and

telling childhood memories, quirks of speech to differentiate them from other

characters, preoccupations going round in their heads as they woke up in the

mornings or went about everyday tasks. The dossiers began as a mass of notes

made from brainstorming sessions, but were sifted, developed, honed down and

refined into useful documents defining each character, which could be consulted

as he or she appeared in each stage of the plot.

My consultant pointed out that screenwriters are advised to ‘always

know what your characters are doing when they’re not onscreen.’ As I worked on

the fleshing out of my characters, I began to have this sense of a relationship

with them, of an imagined life for them beyond the confines of the text, so

that I could work out at any given point in the story how they would react. The

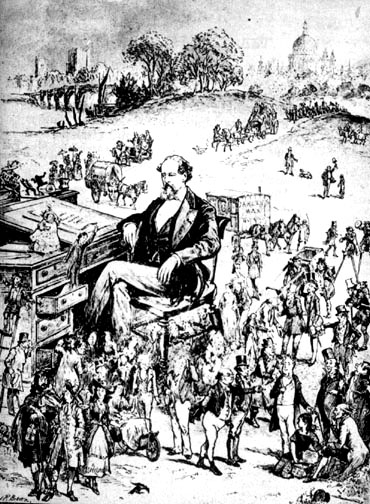

characters took on life. Forgive my upstart cheek in including a picture here of Dickens with his characters...

I now enjoy their

company. I worry that I will miss them when the novel is finished. (Ha! Like

that’s ever going to happen.) Working out their every influence and reaction,

their thought life and the legacy of their past, has made me feel that I know

them the way I know real people. I know that Sarah has always fussed over how

her cutlery drawer is organised; that David would scoff at his sister’s relaxation

tapes and make jokes about ‘whale noise’; that Deb longs to be with people who

knew her before she had a child; that Kim grows her own herbs and watches

rubbish on TV when she is tired; that Mary is profoundly affected by having her

hair done; that Jim bristles at the suggestion that he might put up a satellite

dish; that John Briers touches his receptionist’s palm as she hands him the

post and is gratified by her disquiet, but wants to slap away her look of

revulsion.

Knowing all this, and more, I could work out how each

character would react when under intense stress, or during a calamitous crisis.

I could imagine Deb furious, Sarah fighting for her life, John having sickening

nightmares, Mary losing the will to live, Kim trying to assess her own brain

injury; David crashing out of the house in outrage; Joe sweating through his

pyjamas in terror.

Beware, being too thorough in your character development,

however. Fleshing out your characters can make them so real to you that it affects

your decisions over their fate in the story. When I had finished developing one

character , I liked her so much that I was no longer sure I could bear to have

her come to the end I had originally intended. She was meant to die horribly,

but I didn’t want to kill her, in fact, I wanted to meet her for coffee. Did I

stick to my guns? You’ll have to wait and see...

I feel that I know her already! You are obviously enjoying working with her a lot more. Some good advice was sort and it is now paying dividends. Well done.

ReplyDeleteI wish you the best in layering your novel with depth and perception. There is nothing wrong with alligning your muse with Mr. Dickens -- I do that with Roger Zelazny (someone few but I have heard of.)

ReplyDeleteIf your characters live for you, then they stand a better chance of living for your readers. My blog has pointers for all of us struggling writers. Pay a visit sometime. :-)